Urinary stones

Introduction

Renal stone disease is a widespread condition that affects individuals across all countries and ethnic backgrounds. In the United Kingdom, around 1.2% of the population is affected, with men facing an estimated 7% lifetime risk of developing a kidney stone by the age of 60 to 70. However, the risk is significantly higher in certain regions, such as Saudi Arabia, where more than 20% of men in the same age group are likely to experience renal stones during their lifetime.

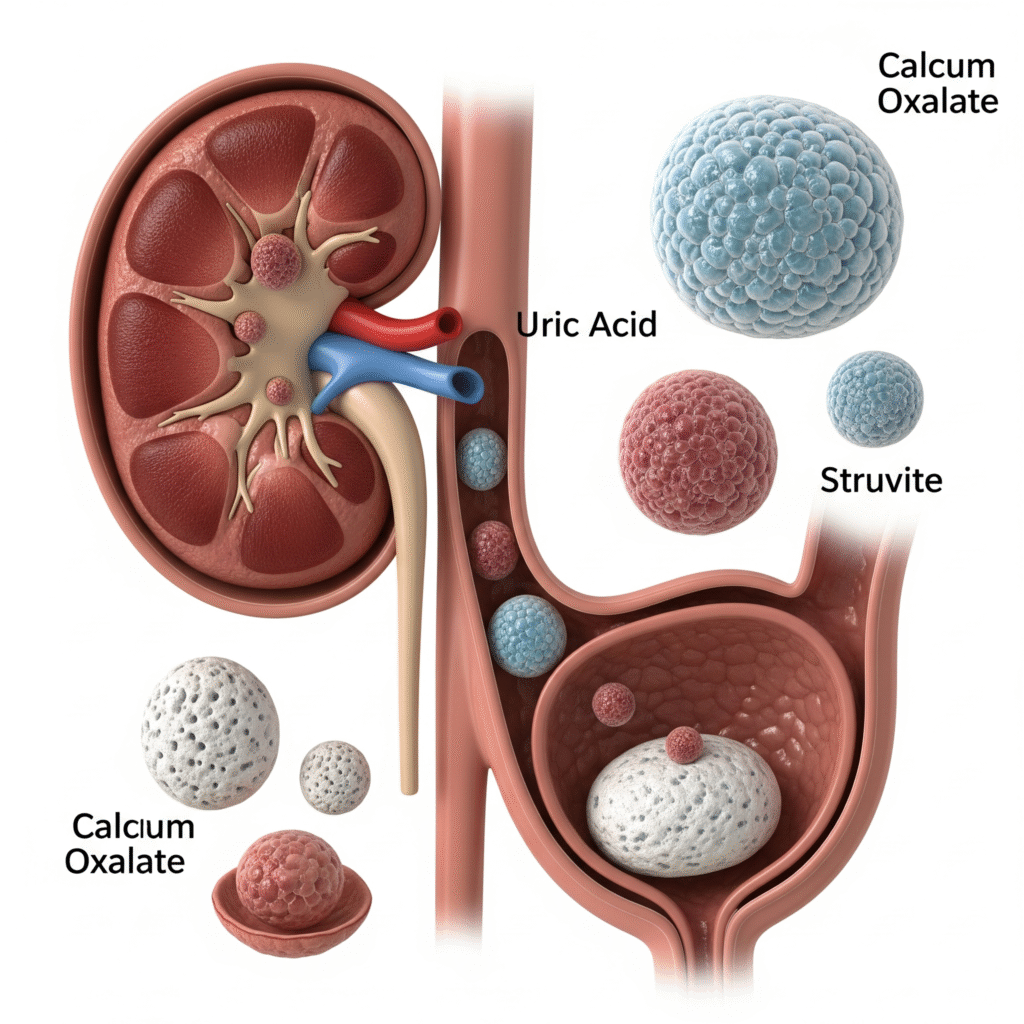

Types of Urinary stones

Calcium Stones

Most common type; includes calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate stones. Often linked to dehydration and high-oxalate foods.

Uric Acid Stones

Form in acidic urine; associated with high-protein diets, gout, and low fluid intake.

Struvite Stones

Infection-related stones caused by bacteria that produce urease; can form large staghorn calculi.

Cystine Stones

Rare stones due to a genetic disorder (cystinuria); occur when excess cystine is excreted in urine.

Causes Urinary stones

- Drinking less water – Leads to concentrated urine, which forms stones.

- High salt intake – Increases calcium in urine, promoting stone formation.

- Family history – Having relatives with kidney stones raises your risk.

- Certain medical conditions – Like gout, hyperparathyroidism, or urinary infections.

- Low calcium diet – May increase oxalate absorption and lead to stones.

- Excess use of supplements/medications – Such as calcium, vitamin D, or diuretics.

- Obesity – Changes urine chemistry and increases stone risk.

Clinical features of Urinary Stones:

Severe Flank Pain (Renal Colic)

Sudden, sharp pain in the back or side, usually on one side.

Pain may move to the lower abdomen or groin as the stone travels

Hematuria (Blood in Urine)

- Urine may appear pink, red, or brown.

- Caused by the stone irritating or scratching the urinary tract.

Frequent Urge to Urinate

Especially if the stone is near the bladder.

You may feel like urinating often but pass only small amounts.

Burning Sensation During Urination

Similar to a urinary tract infection.

Indicates the stone is in the lower urinary tract.

Nausea and Vomiting

Often occurs due to intense pain or blockage affecting kidney function.

Can be accompanied by sweating and restlessness.

Symptoms associated with Urinary Stones

Sharp pain in the side or back

- Pain or burning while urinating

- Blood in urine (pink, red, or brown color)

- Frequent urge to urinate

- Difficulty or interrupted urine flow

- Nausea and vomiting

- Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

- Fever and chills (if infection is present)

Investigations in Urinary Stones

- Patients with symptoms like severe flank pain should be evaluated to confirm whether a stone is present in the urinary tract.

It is important to find out where exactly the stone is located and whether it is causing any blockage to the flow of urine.

About 90% of stones contain calcium and are visible on a simple X-ray. This test is useful for detecting radio-opaque stones.

This is the gold standard investigation, as it can detect about 99% of stones in the kidney or ureter. It gives a clear image without using contrast.

Ultrasound can detect stones in the kidney and signs of blockage like swelling (hydronephrosis). It is especially helpful for pregnant women or those who should avoid radiation.

A minimum set of tests like urine analysis, serum creatinine, and blood tests should be done for every patient presenting with a first-time stone.

Detailed investigations (e.g., 24-hour urine collection) are usually reserved for patients at high risk of recurrence, such as those with recurrent stones or a family history.

If the stone is passed or removed, it should be sent for chemical analysis to identify its composition and help determine the cause.

After a renal colic episode, patients should filter their urine using a strainer for a few days to catch and collect the stone for lab testing.